Just at the foot of St James’s Street, and occupying several adjoining buildings stands Berry Bros. and Rudd, the oldest wine merchant in Britain. They have been selling claret and pinot noir here since 1698. Like so many London institutions and businesses, it has not always been what it is now. Originally it was a humble grocers, a place for fruit and vegetables, things needed for the larder and the kitchen cupboard.

The first owner, appears from the mists of history, a lady by the name of Widow Bourne, by all accounts a shrewd and sophisticated businesswoman. She saw the growing prominence of the London coffee houses, recognised them as centres of gossip, of social and political life, and sensing their pull, she started one of her own here. Alongside the vegetables, were now coffee beans, then tea, cocoa, snuff and spices; the small luxuries of an outward looking city and an expanding global influence. Though Berry Bros. & Rudd is now much older as a wine merchant than as anything else, the sign which still hangs outside is of a coffee grinder, a quiet nod to those early times.

Under any ordinary circumstances, this would have been a difficult business to sustain. But these were no ordinary circumstances. Just across the road, by chance, lived the wealthiest and most influential customers in the country, who had coincidentally just moved in: the royal family. Newly settled after the destruction of Whitehall Palace by fire, the monarch and his family had moved literally next door. And being well disposed toward the finer things in life, this was great news for all the local businesses. This quiet street was suddenly an artery for royal London; courtiers, messengers, nobles and merchants all passed through. The shop adapted and grew, as successful London shops do. Over time, the fruit and vegetables gave way to bottles, the scales to ledgers, and the air filled not with apples and beans, but with cork dust, cigars and the perfume of wine.

One of the scales, which can still be seen today, was used not just for the weighing of goods. The vegetables and the coffee, the sacks and scoops, it also measured people, the stores customers and clients. Its a proper solid grocers scale, one which sits just inside the door, anchored by a sturdy iron beam. There is a small worn seat on one end, and the platform with the weights on the other. It appears people have always been preoccupied with their weight. Long before bathroom scales were commonplace, and for those to whom it mattered most, the wealthy squires and well dressed ladies, all came here for an accurate measurement. The results weren’t forgotten either, they were all written meticulously down.There are old red leather-bound ledgers, known as the Register of the Weights, which date back to when the practice started in 1765. They record in neat ink, the bodily dimensions and deviations of history’s great and most vain. Among the famous faces who have had their weight recorded here, include Lord Byron, the Duke of Wellington, and William Pitt the Younger. A particular amusing entry, or series of entries, belongs to Beau Brummell, king of the dandies, who had his weight recorded here 39 times between 1798 and 1822.

Beneath its rolling creaking wooden floors lie the cellars, descending the narrow stairs you enter a surprisingly vast cavernous space, they are huge and cover the area of around two football pitches. This was where the exiled Napoleon III held secret meetings with his supporters, no doubt knocking back a good Bordeaux or Claret, then over a hundred years afterwards, Queen Elizabeth II held her 89th birthday celebration here with her close family. Now they are busy spaces, used for excellent classes and events. Until the 1990’s, they held well over a million bottles of wine, stacked deep beneath the street, dustily ageing. Few of the thousands of people walking past each year ever suspect that beneath their feet lies one of the most significant private wine collections in the country.

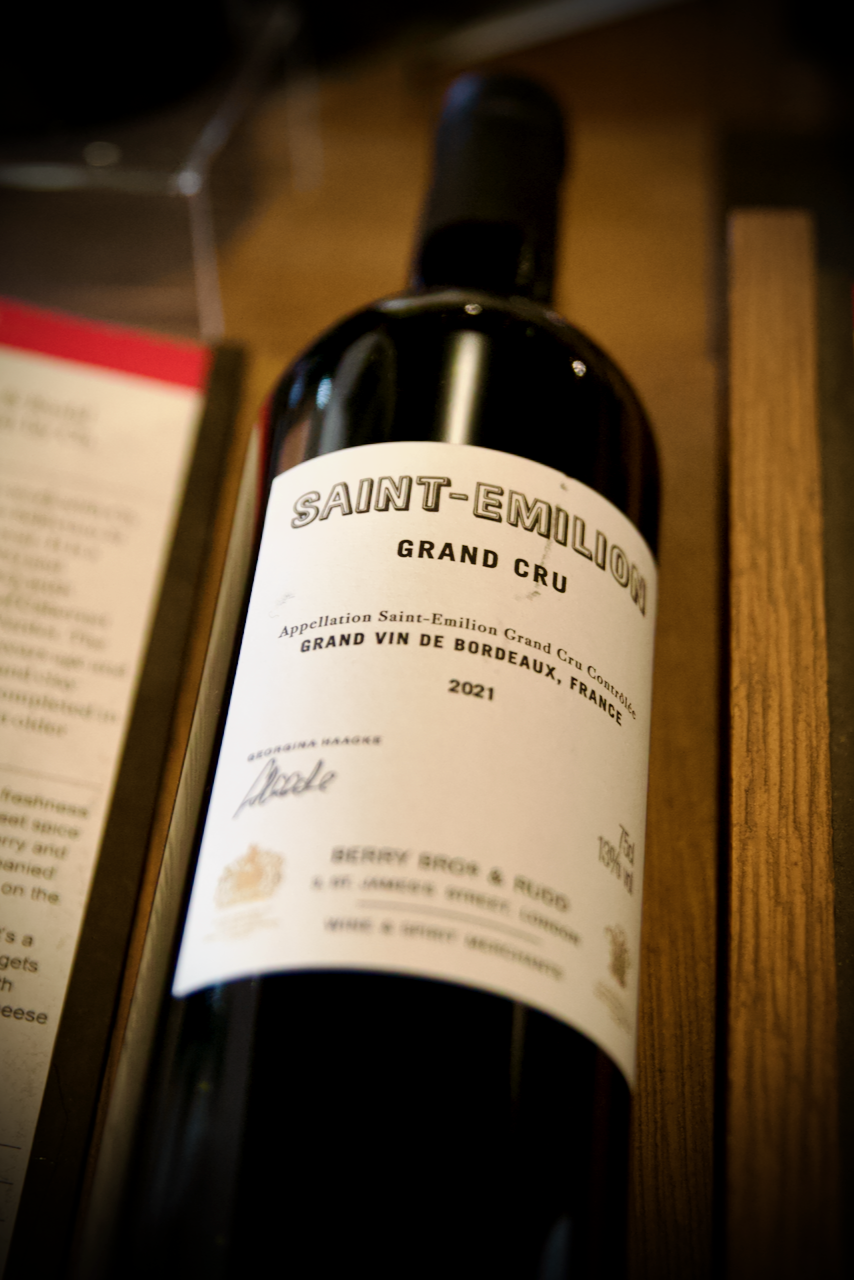

Berry Bros. & Rudd endures, in fact continues to grow, because it has always understood two essentials of business; adapt, always look at what people are after, and, be lucky. It sold what London wanted before London itself knew exactly what it wanted. From humble vegetables, to coffee and tea, to wine and port and whiskey. It did all of this from a position of incredible good fortune, where it stood and still stands today; set opposite a royal palace, and serving a clientele of the elite and the curious visitor, alike. Sensing the importance of its history, people like such things, it has firmly embraced its past in its present. I love walking into its beautiful shop, bringing guests in to have a sample and a chat, before moving on through St James’s. Occasionally I’ll grab a good Claret to accompany a Sunday roast at home. It’s always a pleasure.

Leave a comment