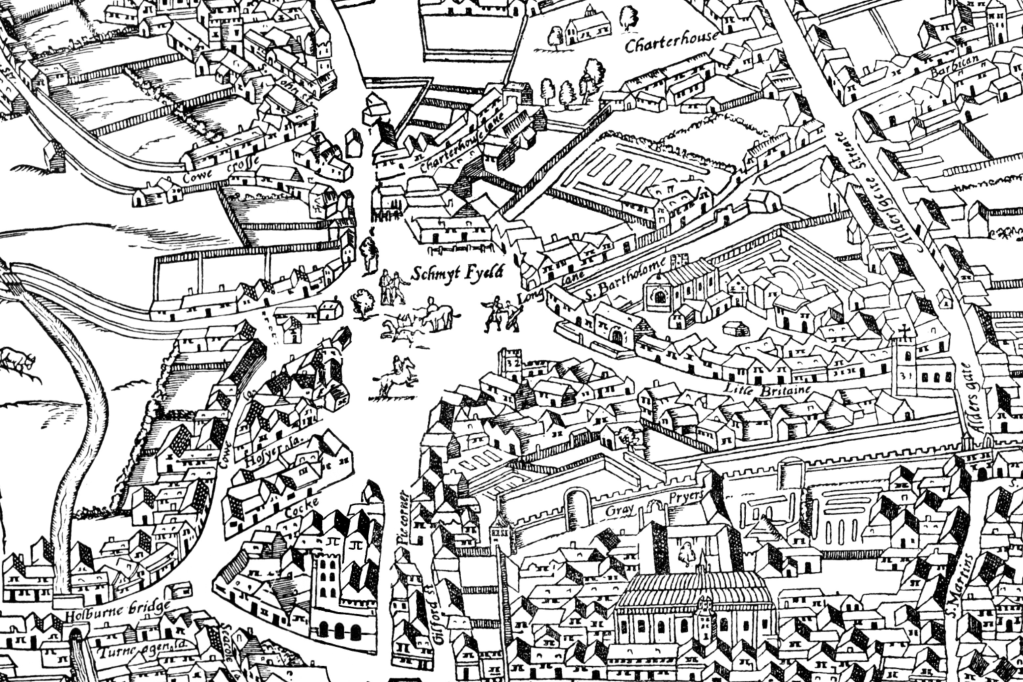

The area Smithfield market occupies is expansive. To truly appreciate this space, you need to stand at the corner of Charterhouse Street, where it opens up to the northwest corner. With the wall of the old pub the Smithfield Tap to your right, you can gaze down past the ornamental towers, the golden stone-brick of the Victorian market and see how the land, level at first, begins to slope into the clearly discernible valley of the lost River Fleet.

Standing there looking around you get a sense of what a big area Smithfield occupies, and you can understand how over the centuries this space has been a place of significance to the population of London.

I like to stand here and think of how this place once looked, perhaps in some long distant medieval summer. How it would have been simple grassland just north of the ancient defensive walls built by the Romans, fringed by a few roads and buildings, the river lined with mills grinding bread for the city, women laundering clothes and laying it out to dry in the warm summer grass. Simple country folk setting up stalls and selling their produce, a little market at the edge of town. There’s always been a market here.

My fanciful daydreams are usually cut asunder by the roar of a refrigerated lorry heading towards Farringdon Road.

Smithfield to me has always had the air of being outside of the city, it feels very different to the streets nearby, despite being swallowed over the centuries through London’s growth. Smithfield is often quiet, perhaps a little forgotten. From the very beginning it was a space beyond.

Now there is so much history here in this little pocket of London, that it would be impossible to fit it all in here, so I hope this will go some way in covering the story, but not everything in any great detail. I hope one day to revisit and delve deeper into different little snippets of fascination. But for today we shall only attempt a broad stroke of the brush.

John Stow, one of London’s first great antiquarians, wrote about the discovery of Roman gold coins found buried nearby. More recent archaeology in the area outside the old city gates has uncovered ancient Roman tombs and graves. One grave at nearby Spitalfields carried the fascinating remains of a young woman who had been buried with great ceremony. Clearly of noble birth, scientific analysis of her teeth and bones suggest she had spent her childhood in Italy. In her ornate lead coffin decorated with scallop shells archaeologists found fragments of Syrian gold thread and Chinese damask silk, perfume containers and phials made of continental-made glass and exquisite jet; movingly her head rested on a pillow filled with incredibly well preserved bay leaves. Its still a mystery as to who she actually was.

During early medieval times, Smithfield was used chiefly as a recreational area where jousts and tournaments took place, and where St. Bartholomew’s Fair, notorious for great merriment and revelry, was held. Amazingly, we have a truly remarkable record of this period. A voice comes out and speaks to us, that of William Fitz Stephen, who in 1174 penned a description of London with incredible skill and detail, probably one of the great pieces of writing concerning London.

‘Also there are, on the north side, pastures and a pleasant meadow land, through which flow rivers, where turning wheels of mills are put in motion with a cheerful sound … immediately outside one of the gates there is a field which is smooth, both in fact and in name. On every sixth day of the week there takes place a famous exhibition of fine horses for sale. Earls, barons and knights, and many citizens come out to see or to buy … here are colts of fine breed; there are the sumpter-horses, powerful and spirited; and after them there are the war-horses, costly, elegant of form, noble of stature … by themselves in another part of the field stand the goods of the countryfolk: implements of husbandry, swine with long flanks, cows with full udders, oxen of immense size, and woolly sheep … after dinner all the young men of the town go out into the fields to play ball. The scholars of the various schools have their own ball, and almost all the followers of each occupation have theirs also. The seniors and the fathers and the wealthy magnates of the city come on horseback to watch the contests of the younger generation, and in their turn recover their lost youth … from the gates there sallies forth a host of laymen, sons of the citizens, the young men indulge in the sports of archery, running, jumping, wrestling, slinging the stone, hurling the javelin beyond a mark and fighting with sword and buckler.’

River Fleet, where Farringdon now lies. Just beyond the city walls Smithfield occupied a great

space and was used by all Londoners as a place for recreation.

King Henry II’s reign. It details significant buildings, customs and the daily lives of its citizens

Smithfield was also known as a place for punishment and execution. Before Tyburn and Newgate, people were executed at Smithfield, sometimes in the most barbaric ways imaginable. In 1305 the famous Scottish rebel William Wallace was dragged naked through the streets of London to the notorious Elms at Smithfield where he was hanged on a gallows. Then, ensuring he was still alive, he was pulled down disembowelled and castrated, his entrails and testicles were burnt in front of him, and then finally he was beheaded and cut into four.

It became a place of continued gruesome punishments and macabre state sponsored retribution. The most famous happened during the thankfully short reign of Queen Mary I, a complete homicidal maniac by all accounts, who was known to all as ‘Bloody Mary’. In the four years of her reign she actively persecuted protestants and tried to return England back to the Catholic Church. It is said that 277 people were burnt to death here – five bishops, twenty-one clergymen, eight gentlemen, eighty four tradesmen, one hundred men, fifty five women and unbelievably four children. Being burnt at the stake was one of the more barbaric forms of execution at that time, although a couple of people were even boiled alive here. It could sometimes take hours for the condemned to die. Often fires would go out and have to be re-lit, in the exposed ground here at Smithfield wind would often turn the flames on certain individuals whilst others were partly burnt. Its hard to begin to imagine the horror of such a scene, yet people would come and watch these spectacles.

Legend has it, as with all legends take with a pinch of salt, that the clearly unhinged Queen Mary I watched the burnings of Protestant martyrs from the gatehouse of St Bartholomew Church, whilst eating a lunch of roast chicken and red wine.

Protestants at Smithfield during the bloody purges of Mary I

As London grew, Smithfield also expanded, and as a place of good grazing and having access to the River Fleet, it began to cement itself by the early Middle Ages as a place for the buying and selling of livestock. Meat has been sold at Smithfield for nearly 900 continuous years. Some street names associated with the market are still in use, such as Cowcross Street, but many others, such as Duck Lane and Goose Alley, have sadly disappeared.

The market, due to demand, was to all intent and purposes becoming a big problem for the city. The population continued to grow through the 1700s and 1800s and they needed meat. Demand was creating enormous pressures. By the 1850’s in a single year 220,000 head of live cattle and 1,500,000 live sheep were “forced into an area of five acres, in the very heart of London, through its narrowest and most crowded streets” to be sold and slaughtered on site. Daniel Defoe referred to the livestock market in 1726 as being “without question, the greatest in the world.” It was most probably also the smelliest and most unpleasant in the world.

Smithfield appears in several memorable scenes from Charles Dickens works, the best being from Oliver Twist. The young boy is dragged through the market under the control of everyones favourite Oliver Reed ruffian, Bill Sykes.

“…and so into Smithfield; from which arose a tumult of discordant sounds that filled Oliver Twist with amazement. It was market-morning. The ground was covered, nearly ankle-deep, with filth and mire; a thick steam, perpetually rising from the reeking bodies of the cattle, and mingling with the fog … butchers, drovers, hawkers, boys, thieves, idlers, and vagabonds were mingled together in a mass… the shouts, oaths, and quarrelling on all sides; the ringing of bells and roar of voices, the crowding, pushing, driving, beating, whooping and yelling; the hideous and discordant din that resounded from every corner of the market … quite confounded the senses.”

The ancient practice of live slaughter at Smithfield ended only in 1852 with the Smithfield Market Removal Act. Sir Horace Jones, the architect responsible for Tower Bridge, designed the present-day market. Work began in 1866 on the two main sections of the market, the East and West Buildings. These buildings made pioneering use of a new modern phenomenon; the railways, the market was built above two lines, enabling meat to be delivered directly to the market, thus freeing the streets of thousands of livestock.

The original layout of the East and West Market buildings was 162 stalls, now only around forty remain. The heart of this complex is largely silent. Change is coming again to this area. By 2025, Smithfield’s Poultry Market will reopen as the new home of the Museum of London, bringing a new wave of visitors, while the Central Market will relaunch as a food hall and co-working space. The meat sellers, the surviving old guard, by 2027 will be moved to a facility outside of the city.

Somehow I’ve managed to write about the history of Smithfield and not mention the Peasants Revolt. That will have to wait for another time.

Leave a comment